What Dopamine Culture Steals From You

Dopamine addiction and Normal Mental Anguish

I’m still thinking about Ted Gioia’s essay from the beginning of the year about dopamine culture. Aside from all of the work Jonathan Haidt has done around The Anxious Generation (which is so closely related it’s practically the same thing), Gioia’s essay might be the most helpful explanation of What Is Going On that’s been written since 2020.

Here is a very basic summary:

Entertainment ate art

Distraction ate entertainment; but now,

Addiction is eating distraction

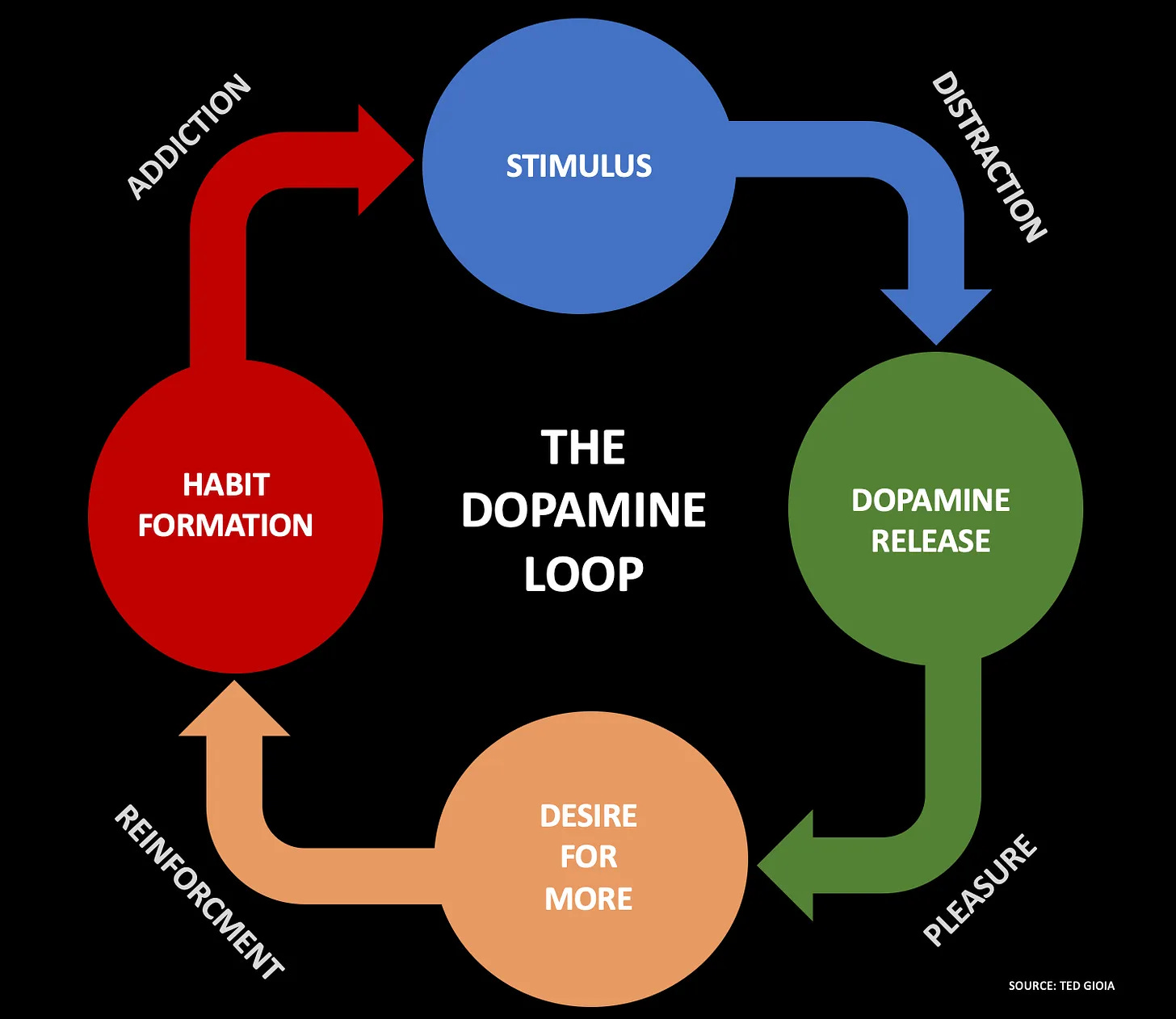

What is the drug we’re getting addicted to? Dopamine. And our dealers are the Big Tech companies. We get addicted to dopamine by getting stuck in a loop where we experience some sort of discomfort that pushes us to distraction. We distract ourselves with online media, which gives us a shot of dopamine in our brains. The dopamine release creates pleasure and a desire for more, which creates a habit of seeking it out. Give into this enough times and now you’re addicted to dopamine and stuck in a loop that is extremely difficult to get out of.

From Jonathan Haidt’s work in The Anxious Generation and others, we know what all of this is doing to us. It’s decreasing connection, increasing mental health issues, gutting childhoods, and stunting normal adult functioning.

The TLDR of this is that this is a very bad way to live your life, but it is also basically the default setting for a huge number of people now.

Dopamine Erosion

The effect of this dopamine addiction is the erosion of someone’s ability to handle Normal Mental Anguish. It’s hard to explain to a dopamine addict that life is hard and full of mental anguish—and that’s normal. It seems as though the category of Normal Mental Anguish is basically gone and the options are essentially some persistent ethereal Zen-like state or a diagnosable yet hardly treatable mental illness. The quickest way to live an unhappy life is to believe in the Zen/Illness binary and not believe that Normal Mental Anguish is a normal part of life and that experiencing it doesn’t mean anything is wrong.

Because discomfort is resolved with distraction and dopamine instead of doing the hard work of pushing through, figuring it out, and actually resolving it (or simply learning to live with it), people never build up the resilience needed to meet the Normal Difficulties of Life. The inability to handle the Normal Difficulties of Life is seen as a broken and unchanging fact of who they are that can only be relieved through professional help. But as Freddie deBour recently pointed out,

My perception, unfortunately, is that a lot of therapists essential treat therapy as 50-minute long exercises in enabling their patients, telling them what they want to hear, and doctor-shopping makes that condition hard to avoid. (If you never get upset about what your therapist tells you, then they’re probably failing you as a therapist.)

There are good therapists who will try to reframe their clients' fixed mindsets and help them see that their condition isn’t unchangeable and that they aren’t fundamentally broken beyond repair, but that’s also a bad business model. Plus, that’s just not what most people are looking for because of the work it requires.

Dopamine is the quickest path to the Zen state, but it’s a cheap alternative to a richly lived life, which actually involves a fairly significant amount of Normal Mental Anguish. The gold is always buried under a thick layer of dirt.

Parenting As Dopamine Deprivation

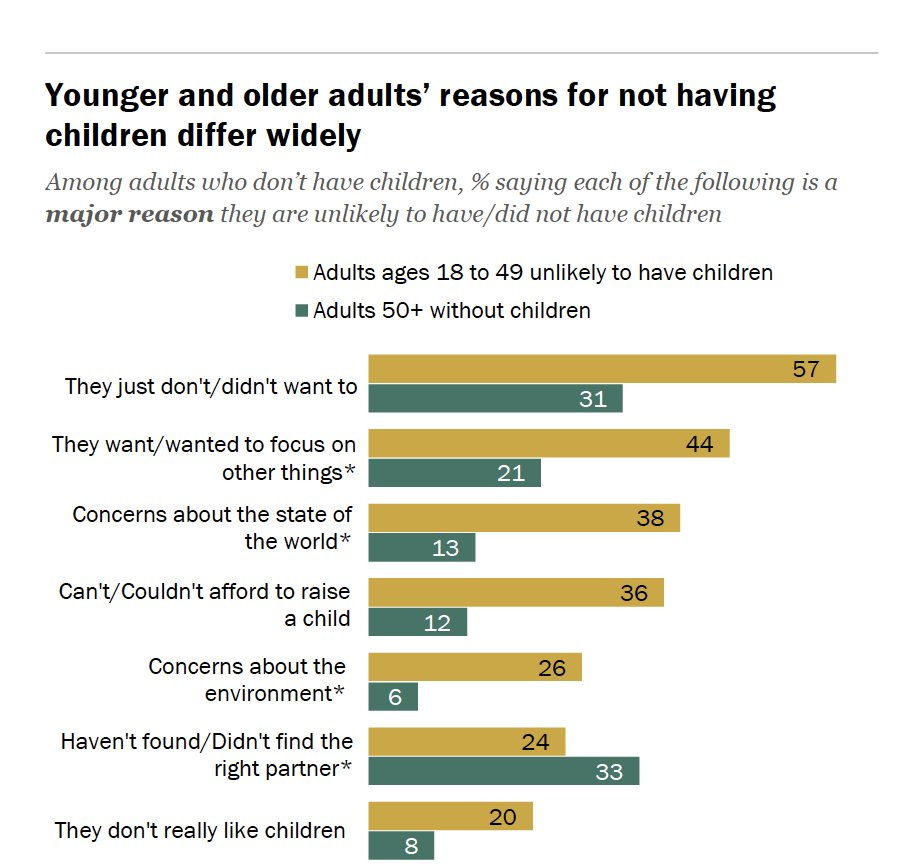

Parenting exemplifies this more than just about anything else. I don’t think it’s any wonder that the top reason young people give for not having kids is simply “I don’t want to.” They rightly perceive that children bring with them a significant amount of Normal Mental Anguish and can’t understand why anyone would willingly bring that into their lives. They mistake a comfortable life with a Good Life and can’t imagine experiencing anything better than their dopamine addiction.

But talk to most parents about how they feel about their children and listen to the difference. Given the choice between their more difficult life with their children or an easier life without their children, how many parents would choose the latter? I’d wager very, very few.

There’s research to back this up. A 2021 article in The Atlantic titled, What Becoming a Parent Really Does to Your Happiness, concluded, “The early research is decisive: Having kids is bad for quality of life.” But the article continues, “Yet [parents] still describe parenthood as the ‘best thing they’ve ever done.’”

That’s because parenting and other similar demanding responsibilities are like excavators digging through the thick layers of self-centeredness until you strike gold. Self-sacrificial love knows depths that dopamine could never fathom.

How do you explain a deep, abiding, selfless, loyal love to someone who has only ever skimmed the surface and had cheap hits of dopamine? How do you explain how getting pooped on and spit up on and barely sleeping most nights is so much better than catching the next season of whatever is on Netflix or Hulu? How do you explain that saying no to the vast majority of things and completely reorienting your schedule around someone else who will almost never say “thank you” is far more rewarding than going out with friends every night?

These things don’t make sense in a dopamine-addicted, professionalized-relief world. They only make sense in the life of someone who aims higher than “feel good, avoid bad” as the end-all-be-all of life. They make sense for someone who wants to live a rich life of existential depth and goodness.

Parenting is not the only thing that does this, but it’s one of the starkest examples because of everything material parenting takes from you and how immaterial its returns are. You don’t make money from parenting. You don’t get fame or notoriety from parenting. It’s a grind. And yet it’s the grind that, if you let it, shapes your character and forms you into the quality of person that money and fame never could.

Dopamine As Love Deprivation

The goal of this kind of life isn’t simply personal virtue, though that is certainly a huge part of it. The goal of this kind of life is a life of love. As David Brooks writes in The Second Mountain, “The very essence of love is dedication.” He goes on, “A commitment is a promise made from love. A commitment is making a promise to something without expecting a return—out of sheer lovingness.”

Dopamine culture can’t give you that. Don’t like the show or video you’re watching on Netflix, YouTube or TikTok? Start a different one. Keep scrolling.

Don’t like that person’s take on Twitter or Instagram? Unfollow them.

A life of love inherently requires others. Love, by its very nature, requires both the Lover and the Beloved. Love requires another to give it to you. You can have self-respect by working hard and carrying yourself with integrity and dignity, but you cannot have love without another who loves you. And love between people requires commitment, and commitment requires work, and work involves Normal Mental Anguish.

If you hollow out your life of commitments, you’ll drain your life of love.

The trade someone makes when they become a dopamine addict is bigger than simply trading discomfort for comfort; it’s trading love for apathy. Or maybe love for outrage. Or love for paranoia. Or loneliness. Or maybe all the above.

Once you understand the tradeoffs, who would choose such a life? Wouldn’t you choose something different? Something better?

Only a loveless culture would tell you to love yourself more than it tells you to love others. Only a loveless culture would encourage you to forgo all of the things that foster love and normalize all of the things that deprive you of it.

Life With Normal Mental Anguish

It’s a tragedy that one of the biggest lessons lost today is that the way to a Good Life is through the path of Responsibility and Commitment and that those Responsibilities and Commitments necessarily involve Normal Mental Anguish and experiencing Normal Mental Anguish is not a bad thing but is actually a good thing.

We don’t have to give a label to Normal Mental Anguish. There is no pill for it. And the best treatment might just be talking to a friend about it and hearing them say they experience it too. Or it’s finding a single quiet morning or evening to sit in quiet for a short time and allow it to pass over you. Maybe it’s going on a run or to the gym and being more in our bodies than we are in our heads. It could be learning something to try and get a grip on whatever the particular anguish is. It’s almost certainly prayer and allowing scripture to fill your imagination more than a never-ending feed of anxious posts. And a good night's sleep goes a long way all on its own.

Sometimes life goes beyond Normal Mental Anguish. It might be Suffering. And it might be Actual Mental Illness. But I’m afraid our dopamine culture has collapsed these categories into a singularity that makes it nearly impossible to distinguish between them. I guess my hope is that we would work to roll back the tape, break our dopamine addictions, and make Normal Mental Anguish our square one and go from there.

There is nothing wrong with feeling bad sometimes or even a lot of the time. We go through seasons of not sleeping well, of being more busy than we would like to be, of things not going our way, of missing opportunities or losing security. We lose loved ones and jobs, we have newborns and unexpected illnesses. As many have said, adulthood is constantly saying, “We should do this when things slow down,” and things never seem to slow down.

So we must bear life. One day at a time. Committing ourselves to God and to one another to help bear the Normal Mental Anguish of life. Dopamine culture reflects yourself back to you in the black mirror of the screens it distracts you with. It isolates you and sucks you into its distortion zone. But Love calls you out. It surrounds you with others. It requires things of you. You could never quantify what it gives back to you, but once you have it, you wouldn’t trade it for anything.

I’ve written a book about deconstruction. It’s called Walking Through Deconstruction: How To Be A Companion In A Crisis Of Faith. It’s deeply personal, but it’s not a memoir. It’s an attempt to serve the church; to help the church understand what deconstruction is, what causes it, and how to walk with people who are experiencing it.

So so good. I appreciated the dopamine tie-in to parenting. I saw someone else mention recently how parenting is one of the few remaining endeavors in life that truly require something intense of of us physically and emotionally - and fewer and fewer have been prepared for such a challenge, if they have have been coddled or self-cocooned in frictionless lives.

beautiful